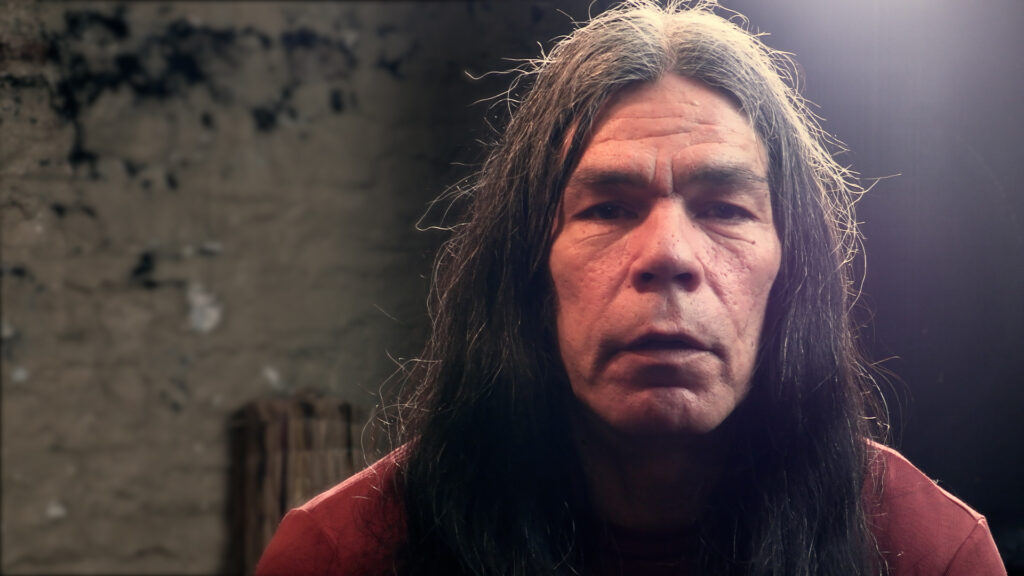

Learn about Canadian persecution of Indigenous communities from Bristol’s Dark Cloud

Jake Mason’s short doc tells the tragic story of Makadayannaquad, a survivor of the Sixties Scoop

This is a short documentary about Makadayannaquad, which translates to Dark Cloud. Dark Cloud is one of the last Chippewa people to tell his story after being taken from his home in Thunder Lake by Canadian authorities during the Sixties Scoop, which saw Indigenous children taken from their families and communities to be placed in foster homes or adoption.

It’s a heart-wrenching story which encourages us to ask the questions: why is belonging still considered a privilege? And why despite the tireless protesting in Canada does the destruction of indigenous land and lives continue under the name of capitalist progress?

You may have seen Dark Cloud without even knowing it: in honour of Dark Cloud and the Chippewa people, Bristol-based artist Tronic painted a mural of him on a road leading from Bristol to the M32 for thousands of passersby to view.

We caught up with filmmaker Jake Mason to get his thoughts on why he believes sharing Dark Cloud’s story is so important. He touched on inclusivity and the importance of awareness around how very current these issues are.

Tell us a bit about you and your work.

I’ve always remembered having an immense curiosity and excitement towards movie-making. I made short little horror films with my friends from school and youth theatre. I self-taught through books and YouTube.

After leaving school and enrolling for media production at Weston College I really stretched my abilities, making my first documentary and commercial video. My final major project was a thirty-minute crime/drama that I wrote, directed, filmed and edited.

Leaving college, I started a film production degree at Screenology. I never wanted to go to university to study film because I wanted to make films not study them. However, Screenology offers a very unique experience which is flexible and independent. You could book an extensive amount of great quality equipment any time, including out of term and over the whole summer. They encouraged projects and networking outside of the University.

Why did you want to make Dark Cloud?

Screenology briefed us to make a five-minute documentary back in February 2020. I was lucky enough to hear about Dark Cloud, the only Native American man living in Bristol. As naive students, we had no idea what we were going to learn. All I knew was he was very unique and his story would trump my classmates’.

Why is it important stories like this are told?

I knew relatively nothing about the state of Indigenous circumstances in Canada. I have distant family in Canada on my mother’s side. My mother told me of the reserves and reparations for First Nation people, and I thought the injustices towards Native American people had long been resolved.

This is far from the truth – there are still laws that allow racial discrimination in Canada. Business owners have the right not to serve Indigenous peoples and although many establishments in the cities today don’t discriminate, it is still within their right to. This happened to Dark Cloud in 2018, when he first visited his adopted brother after 47 years of being out of the country.

Storytelling and movies have a massive influence on our values and self-esteem growing up. I know this as a gay man, I never felt represented in media as a child. It’s why, as a child, I thought people wouldn’t accept me, although I was very fortunate to live in the UK where homosexuality is legal and there are protections. I emphasise the importance of inclusion of every ethnicity, culture, gender and sexuality in children’s television and education. It is much better today, but in the early 2000s, there was a complete lack.

How did you approach making the film and what did you learn in the process?

Having only made one documentary before, I knew this wasn’t my strength. I just jumped in the deep end – there wasn’t much time for research and structural planning. It was more trial and error of how to tell a story within such a large topic in such little running time.

After meeting Dark Cloud and hearing his story for the first time, I was blown away about the lack of coverage on the topic. Hardly any Western media outlets were covering this.

I researched, reshot, got criticism and developed the edit over six months until I was satisfied with the fifteen-minute film published today. The biggest problem for me was how to structure the story and make it relevant.

What would you like for people to take away from watching the film?

I would like people to change their attitudes. Ignorance is bliss but it fuels injustice. People shouldn’t take their rights for granted and they should make time for protecting other people’s rights. Not that they haven’t for many causes – but the Canadian attitude towards First Nation people is out of line with their values.

I feel that the media has failed the First Nation peoples in it duty to hold the government to account. The mainstream media has an agenda and it really makes me angry that the UK government and the Commonwealth didn’t do a single thing about the Sixties Scoop. An example of the effect of what a very well-documented issue can have is the eventual sanctions that were applied to South Africa to force the end of apartheid.

I want people to take the Black and Indigenous Lives Matter movement seriously and to further educate themselves and have conversations with their family and friends. I hope to inspire a change in attitudes.

Do you have any advice for people thinking about making their own documentary?

If you are a young person who wants to make a documentary today, my advice is to just start. It’s what I did, I kept making mistakes and re-shooting and re-editing the film. And when I thought everything was good enough I reached out for criticism. There is always something to be improved and the final cut of Dark Cloud is not perfect and neither is any other film, professional or not.

If you don’t have the equipment I highly recommend reaching out to other aspiring filmmakers you could work with. Cahootify is a brilliant local platform facilitating collaboration in the South West of England. They might own camera and sound equipment or study at a University with that access. Even if that fails, camera phones are good enough for picture quality with another phone recording sound as close as possible to your subject.

What’s next for you?

I really wasn’t in the right place to make this film physically and intellectually. I needed much more time to research and to be able to travel to Canada to really get it more accurate and entertaining. However, it is what it is, and I’d rather have a film than no film.

Documentation of the Sixties Scoop is growing and I would like to be a part of this. I hope to continue to amplify this under-represented topic. I’m writing a feature screenplay, titled Split Feather, an adventure/biography about Dark Cloud’s life. Split Feather is the term used by First Nation people to describe victims of the Sixties Scoop. The screenplay would tell a story based on the events of Dark Cloud’s life, but structured for the mainstream market.

Furthermore, Dark Cloud and I are making plans to travel to Canada together and make a new documentary on the present issues facing First Nation people. The trip will double-up for research on writing the screenplay.

Find out more about Jake’s work here.