How music video makers are evolving to keep up with TikTok

Mabel talks us through how traditional videographers are keeping pace with super popular self-made makers

Over the last six months, musicians have continued to release singles and albums despite the coronavirus crisis – and while you’d expect the quality of music videos to have suffered, that hasn’t happened so far. Production crews used for music videos usually consist of at least seven people, but social distancing rules have deemed this impossible, so now a lot more of the creation has now been left up to the artist themselves. Luckily, the app TikTok has also boomed during the coronavirus crisis, meaning that self-creation and imaginative videography hacks have become a lot more fashionable. Lo-fi aesthetics have even returned, giving new music videos a lot more leeway.

TikTok has also boomed during the coronavirus crisis, meaning that self-creation and imaginative videography hacks have become a lot more fashionable.

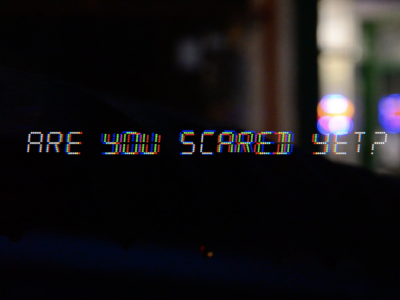

It seems that the art directors that work alongside artists have taken this in their stride. Popular RnB singer Jason Derulo even substituted a music video for a live stream on YouTube to release his songs over the summer. Vibrant LEDs provided lighting by his pool in the evening, demonstrating imagery that’s similar to the fully-produced music videos in the charts. All filmed in the evening or at night, they’re lit by colourful strobe lighting, city lights or a mix of both, similar to the look of popular Gen Z and millennial TikTokkers’ rooms where they film their videos. Producers have drawn on this aesthetic while still using high quality, professional equipment. Consciously, this does not necessarily remind the audience of TikTok, but should trigger the serotonin that links them to it.

They’re lit by colourful strobe lighting, city lights or a mix of both, similar to the look of popular Gen Z and millennial TikTokkers’ rooms where they film their videos.

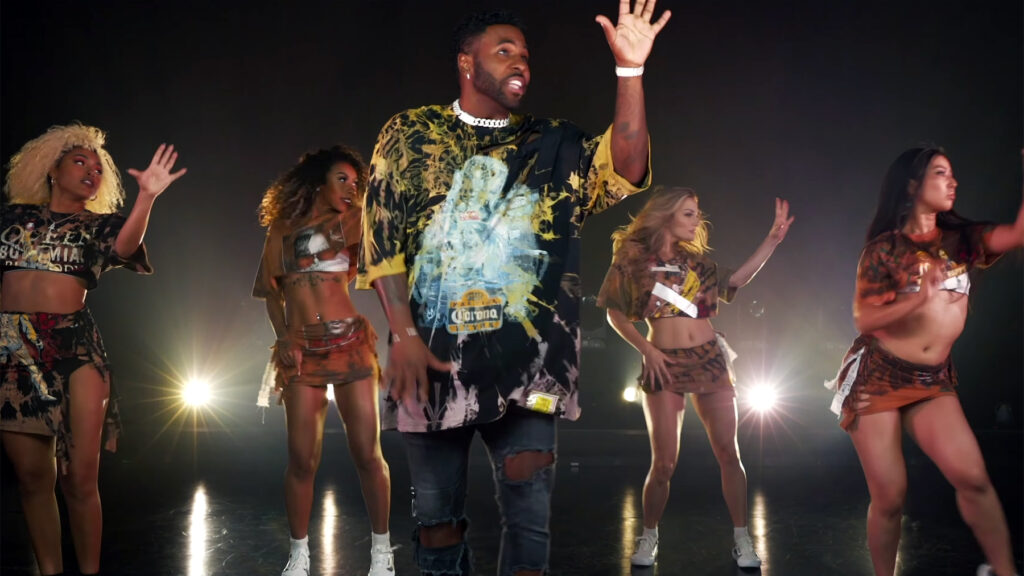

Average attention spans have decreased alongside the growth of social media, meaning that keeping the video moving is not only the job of the editors and VFX editors now – a lot more responsibility is on the videographer to make a video interesting before the editing is added. With the return of lo-fi and self-created works, the audience appreciates raw creativity without special effects. Scrolling through a TikTok ForYou page, your eyes are constantly kept busy by movement – mostly in the form of dancing to the riffs of viral songs – meaning that it can now take a lot more work to keep someone interested. Videographers have therefore used excessive camera movement, paired with dancing similar to that seen on TikTok. For example, Jason Derulo used his own TikTok dance in part of his music video for Take You Dancing (2020), while the camera moves back and forth and cuts to a new angle. Each of these tiny shots only last two to four seconds each, the camera uses a great deal of movement in each. Popular music videos have always been fast paced, but when one compares a music video released in 2020 to a music video released in 2009, the difference is vast. Sexyback, Justin Timberlake (2009) is a fast-paced song, but the colourscheme is new-age (silvers and silvery blues), and the videography includes some still shots. Take You Dancing, Jason Derulo (2020), has a vibrant colour scheme portrayed mostly through the LED lighting, and every one of these shots contains a lot of camera movement. The silver and silvery blue colour scheme in Sexyback fits with the time period of extreme, fast technological development (90s-00s) and the rejection of old technology, therefore engaging the young viewers at the time who were experiencing immense changes in day-to-day living. Now, in 2020, when TikTok is constantly growing and has provided a lot of comfort for lots of people, the carrying over of its LED nighttime aesthetics and higher movement shots to mainstream music videos is engages the younger viewers of today; Blinding Lights, The Weeknd, has been a viral TikTok song this summer, and is still in the top ten. Older videos such as The Way I Are, Timbaland (2009), used the new-age look that attracted viewers of the time, with more cinematic lumetri colours, as opposed to Don’t Start Now, by Dua Lipa (2020), which relies a lot more on predominantly red, purple and blue lighting, now considered a futuristic look in comparison 2009 videos.

Scrolling through a TikTok ForYou page, your eyes are constantly kept busy by movement – mostly in the form of dancing to the riffs of viral songs – meaning that it can now take a lot more work to keep someone interested.

Clean transitions have been something creators have been aiming for this summer on TikTok and this has been the same in music videos – all of the three to four second shots in new music videos are edited with extremely clean cuts, however the light leaks were used as a transition a lot more in the music videos of 2009. If not directly used from Premiere Pro, the look of white lights flashing between shots was created organically in the studio, noticeable in Timbaland’s The Way I Are (2009), for example.

From 2009 to 2014, mainstream music videos featured old 90s televisions, usually smashed or displaying the white noise screen, such as in Pretty Hurts, Beyoncé (2014), and Sexyback. In the midst of the new-age look of the videos, this seems to be a rejection of the past and of old technology. But featuring old-fashioned aspects of life is not an uncommon technique in music videos. A masked ball is featured in Dua Lipa’s Don’t Start Now (2020), but with the juxtaposition of modern dancing and full-colour camera quality. When the past is referenced in music videos today, it tends to be much older, and a glorification of it instead of a rejection. Younger generations today have grown up with advanced technology and have not experienced its initial development, so its existence is used to reference the ‘simpler times’ they wished they had experienced that have been romanticised by the films, books and TV programmes that represent them now.

With the return of lo-fi and self-created works, the audience appreciates raw creativity without special effects.

Ever since music videos became widely recognised as an artform and a way of expressing a narrative, they have been evolving with the culture around us. Art directors express society and politics sometimes not even consciously, but creative projects are always an expression of the times. It is inevitable that music videos become outdated, but they still always express the world we once lived in. I think this will be invaluable for future generations.

What do you think? Have music videographers done enough to keep you interested? Let us know in the comments.