Is Coronavirus transforming political possibilities in the UK?

Rupert looks ahead to what might happen next in our pandemic-struck political landscape

On 23rd March 2020, Prime Minister Boris Johnson addressed the nation from 10 Downing Street. He told us we “must stay at home”, announcing a UK-wide lockdown in an attempt to reduce the spread of Covid-19. In response, much of the tabloid press habitually invoked the era of the Second World War, in particular the Blitz – the German bombing campaign against Britain that lasted from September 1940 to May 1941. In popular memory the Blitz is remembered as a moment when Britons stood side by side, regardless of class,and instead of crumbling, the stoic British people stood alone – you could say they kept calm and carried on. While there were undoubtedly individual acts of kindness and bravery to celebrate during that time, the ‘Blitz Spirit’ was largely a necessary product of wartime propaganda. In reality, Britain never stood alone. It was bankrolled by American money and propped up by easily exploitable colonial manpower. The much commodified ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ poster that has become so popular recently was never circulated during the war. It is both inaccurate and reductive to compare our current crisis with this romanticised vision.

In reality, Britain never stood alone. It was bankrolled by American money and propped up by easily exploitable colonial manpower.

The real analogy, if there is one, is in the chance we now have to transform our politics. In Britain, the mobilisation of a wartime economy showed that it was possible to centrally plan and run an economy in times of emergency. It demonstrated that the state had the capacity to ensure the entire population was fed, employed and cared for. This normalised the idea that the state can play a major role in directing the economy and was reflected in post-war planning and public opinion. For instance William Beveridge, a senior civil servant, produced a report on Social Insurance and Allied Services, which declared war on the five evils of Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness. He viewed the state-driven model of economic planning and full employment as a unique opportunity to transform society. The Beveridge Report sold 600,000 copies by 1944. Furthermore, the Labour Party won a landslide victory with a radical manifesto – which itself sold half a million copies – promising to nationalise major industries and implement far-reaching social reforms, including universal health care. This signalled a shift in the role of the state in society – and in our current crisis we find ourselves in a similar situation. The role of the state is being reconfigured, and in the process, undermining sacrosanct faith in the role of the market over the state. As in 1945, this offers a unique opportunity to change society for the better.

The role of the state is being reconfigured, and in the process, undermining sacrosanct faith in the role of the market over the state.

Instead mobilising a wartime economy, Britain has demobilised the economy in the face of a public health emergency. The Government in a volte face of their previous ‘herd immunity’ strategy, announced a nationwide lockdown. This was in response to an Imperial College study which estimated up to 250,000 deaths if the government failed to implement it. As part of this change of policy the Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, announced a series of unprecedented measures to ensure the public could adhere to social distancing regulations. On March 17th Sunak located the elusive ‘magic money tree,’ announcing £330 billion of state-backed loans for business, along with £20 billion in tax breaks and government grants. Sunak vowed on 20th March that the Treasury would pay 80 per cent of the wages of workers temporarily unemployed, up to £2,500 a month. He also raised Universal Credit by £80 a month. These measures were commendable and necessary. The Tories are now borrowing and spending on a scale which a few years ago current cabinet ministers would have castigated. This marks a significant, pragmatic change in policy and, potentially, longterm mindset.

On March 17th Sunak located the elusive ‘magic money tree,’ announcing £330 billion of state-backed loans for business, along with £20 billion in tax breaks and government grants.

Sunak’s measures demonstrated that the state can still play a major role in the economy and, where necessary, splash the cash. During the 1945 General Election campaign, Winston Churchill’s hysterical claims that Labour’s proposals to nationalise industries, ensure full employment and implement social reform would lead to totalitarianism were viewed by the public as ridiculous. After all, they had witnessed the success of these policies during the war. Similarly, ridiculous claims were continually made in the years prior to the Covid-19 crisis. The British public were told that moderate tax rises to invest in the economy and state planning was ‘Marxist’ radicalism which would wreck the economy. The public were told, in justification for austerity, that there was ‘no magic money tree’. The apparent self-evident truth that the role of the state is to stand aside and let the market regulate society, has been revealed to be what it always has been: a political choice.

Sunak’s measures demonstrated that the state can still play a major role in the economy and, where necessary, splash the cash.

The spotlight of Covid-19 has – at a tragic cost – highlighted both the ability of the state to act decisively for public good, but also the many failures of our current political settlement. Britain’s death toll from Covid-19 at time of writing stands at 34,639, the highest in Europe. This is the result of short-term policy failure, such as initially failing to act on the World Health Organisation’s advice to ‘test test test’. It is also a damning indictment of austerity policies. Since 2010, 20,000 general and acute beds have been slashed from the NHS. The number of nurses were cut, with a shortfall of 40,000 and social care cut by £7.7 billion. It is not crude to suggest a correlation between such devastating cuts and Britain’s sky-high death toll in comparison with other highly developed nations.

The spotlight of Covid-19 has – at a tragic cost – highlighted both the ability of the state to act decisively for public good, but also the many failures of our current political settlement.

In the immediate future things will not go back to ‘normal’ until a vaccine is developed and rolled out on mass scale. During the War emergency measures to mobilise a wartime economy, such as full employment, stayed in place in peacetime. It is credible to suggest emergency measures introduced to deal with Covid-19 could also stay in place. This may be especially true given the public desire for higher public spending and an interventionist state, reflected at the 2019 General Election. Measures such as the housing of homeless people in a bid to stop the spread of the Coronavirus have suddenly meant thousands of people now have a roof over their head. Without the stress of not having a warm bed, many have been able to start getting their lives back together, finally having a safe space in which to tackle mental health issues and addictions and look for work. While this housing is only temporary, with councils commandeering hotel rooms, it has demonstrated that solutions can be found with political will. It will be politically difficult for the Government to simply turf these people out when ‘normal’ life returns.

Measures such as the housing of homeless people in a bid to stop the spread of the Coronavirus have suddenly meant thousands of people now have a roof over their head.

Similarly, the furlough scheme has demonstrated that it is possible to offer generous unemployment insurance. The introduction of this would bring Britain in line with other European nations like the Netherlands, where citizens are paid 70 per cent of their previous salary for up to 38 months. Germans receive 60-67 per cent of their salary for a maximum of 24 months. French citizens are paid 57 per cent of their salary for 24-36 months. If such provisions can be provided during this crisis, it is difficult to imagine the public accepting a return to the withered excuse of the welfare state we experienced before.

This pandemic has demonstrated the ability of the state to act positively to ensure the security of its citizens. This gives us a chance to rethink what governments are for and what is deemed politically possible.

This pandemic has demonstrated the ability of the state to act positively to ensure the security of its citizens. This gives us a chance to rethink what governments are for and what is deemed politically possible. In light of this, the UK should consider radical state-led policies to tackle not only social and economic inequalities – which have grown exponentially since the 1980s and been compounded by what Polly Toynbee and David Walker dubbed ‘The Lost Decade’ caused by austerity – but importantly climate breakdown. This requires a foundation of a well-funded welfare system and NHS. Other measures might take the form of higher taxation on the wealthy, including a wealth tax, and, perhaps – in some form – Universal Basic Services and Income. In order to reach the target of capping global warming at 1.5 ℃ we will have to transition towards a low to zero-carbon economy. This will require dealing with job losses from polluting industries, public investment in low-carbon infrastructure and a serious industrial strategy to create new Green jobs. This is not possible without strong state guidance.

In this time of uncertainty it is certain that as the dust settles the state will play a much more significant role in the direction of the economy and society. While this trend was already in motion, the Coronavirus pandemic has, by necessity, accelerated its process.

In this time of uncertainty it is certain that as the dust settles the state will play a much more significant role in the direction of the economy and society. While this trend was already in motion, the Coronavirus pandemic has, by necessity, accelerated its process. From this position there will be debates over how to deal with the coming economic fallout of the crisis. With the IMF predicting the ‘worst economic downturn since the Great Depression’, there will be some calling for austerity 2.0. However, it is unlikely for this to be politically viable. This could provide fertile ground for the Labour Party to recover from their disastrous 2019 General Election defeat. Both their 2017 and 2019 manifestos proposed state-driven investment and an industrial strategy. In this changed environment, these policies may seem more appealing. It is far from inevitable that this will benefit Labour. Labour’s 1945 election victory was in large part due to its successful role in the wartime coalition showing itself to be a patriotic and a credible governing party, something the party wasn’t seen as in 2019. This is more difficult as Boris Johnson – perhaps learning from Churchill getting the ‘Order of the Boot’ in 1945 – has shown the ability to move left on the economy. The most recent budget included the largest state-led infrastructure investment since 1992, not to mention the recent emergency measures. Moreover, there has clearly been a rhetorical shift at the top of Government, from Boris Johnson commenting that “there is such a thing as society”. This is a clear break from Tory demigod Margaret Thatcher’s hyper-individualism. It is clear the Coronavirus pandemic has, in the same way as the Second World War did, transformed what is deemed politically possible.

What do you think our politics will look like in the wake of Coronavirus? Let us know in the comments.

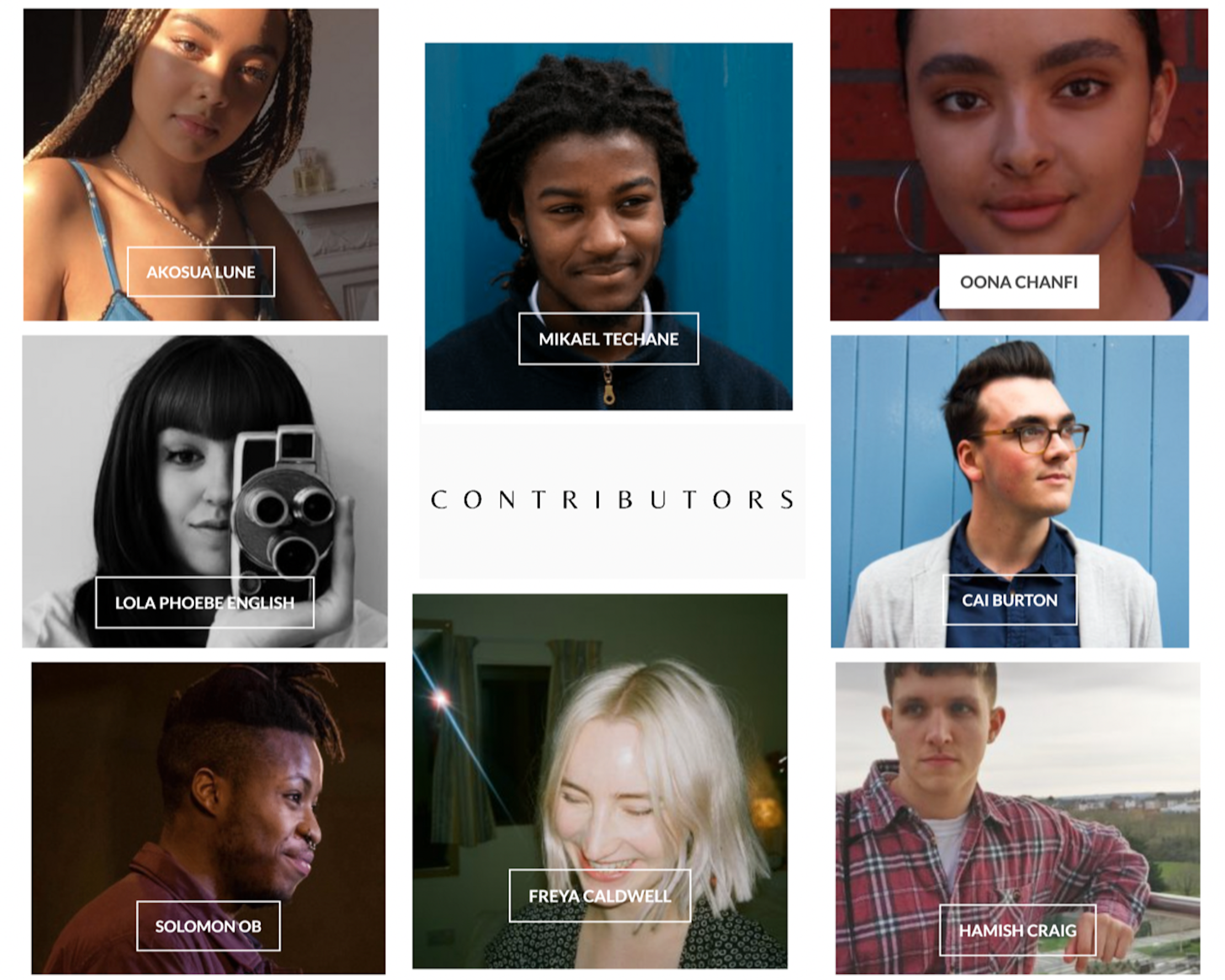

About Rife