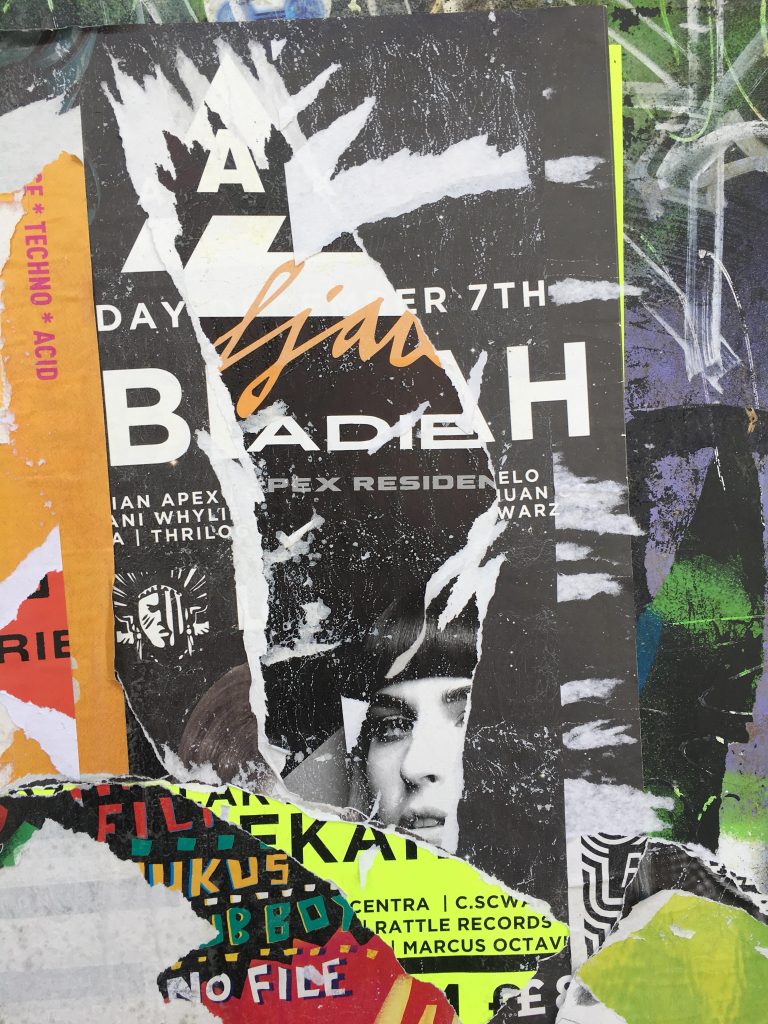

Meditations on Bristol’s Poster-Plastered Walls

Freya studies the overlapping visual history of Bristol’s live music scene she sees in the streets

Palimpsest (noun): a textual term referring to the surface upon which an earlier piece of writing, having faded into near disappearance, has been effaced by a later text. Printed onto the same surface, the two texts thus exist simultaneously; the original text remaining faintly readable, though almost entirely overwhelmed by its newer companion. The texts may, perhaps, share no obvious relation, other than the page or surface of their imprint. Yet this sharing of space unlocks an unlikely relation between the two artefacts.

Each poster bleeds into the next in a cacophony of dates, locations and line-ups: a mosaic of symbiotic creative outputs.

Positioned in the heart of Stokes Croft, and stretching the length of the construction site concealed behind, there is a temporary, corrugated wall plastered with layer upon layer of accumulated print: large neon posters decorated with heavy black type; aggrandising black and white portraits of touring DJs; photocopied collages; and smaller stickers and tags, promoting labels and art collectives, filling the rare gaps. By passing this nameless wall on an almost daily basis, and observing its elusive developments, I have come to view the wall as a palimpsest that is symbolic of Bristol’s thriving print culture, and a visual measure of the city’s ever-evolving music scene.

As events come and go, the layers of promotional material have built up. In places these layers recede, stripped away in a bid to return to the galvanised surface, unearthing an archive of previously hidden print. Each poster bleeds into the next in a cacophony of dates, locations and line-ups: a mosaic of symbiotic creative outputs.

Photography by Max Aldous-Fountain

Yet it would be a mistake to view such a condensed, over-flowing space as purely collaborative, for there is also a healthy competitiveness at play. Studying the surface of the wall, you can see instances in which posters, whether clumsily or with cruel intent, have been prematurely pasted over. Adding one’s event to the pile is fundamentally an act of claiming space: physically, upon the wall itself, and symbolically, too. For “postering” functions as an assertion of an individual’s right to make space for their own expression within an already crowded scene, exposing one’s creative projects as worthy of recognition alongside, or even above, the rest. With this knowledge comes the awareness that your mark too will soon be covered up, effaced.

Adding one’s event to the pile is fundamentally an act of claiming space: physically, upon the wall itself, and symbolically, too.

Indeed, this concept of effacement, of overwriting the work of another, is a practice woven deep into Bristol’s creative fabric. The street art that famously decorates reams of the cityscape is, in its own right, a form of palimpsest. The fundamental appeal of paint applied directly to a city’s architecture lies in its uncertain existence – its triumphant ephemerality. Of course, there are certain pieces that have, against the odds, survived years of exposure – Banksy’s infamous Well Hung Lover is one such piece – yet no work is totally exempt from the palimpsestic cycle. For even Banksy’s hanging lover has suffered the defacement, or rather the artistic addition, of splatterings of blue paint. But it is precisely the acceptance of this temporality, this levelling notion that no artist’s work is guaranteed to remain untouched, that provides the vital impetus for constant regeneration.

Photography by Max Aldous-Fountain

While most posters are destined to fade from exposure, covered over by those that follow, they are memorialised in their encasement below the immediate surface: a brief moment in time captured and preserved by its successor, a means of recording the otherwise temporal, experiential nature of the events they advertise.

Where many favour the neat chronology of events advertised through platforms such as Facebook – which attach themselves to an infinitely renewing calendar of ‘past’ and ‘upcoming’ attractions – the memory of these digital events, lacking their own physical space, seems somehow more fragile: they soon melt away, their sell-by-dates passed, subsumed by a torrent of auto-updating online content, slipping silently into the electronic ether.

These posters, collecting in locales particularly rich in creative output, map heavily trodden routes built up over time.

There is thus a certain sadness in the general movement away from print in favour of its online counterparts. For online space is a no-place, detached from the natural routes taken on foot by a city’s traversing inhabitants. These posters, collecting in locales particularly rich in creative output, map heavily trodden routes built up over time. The arrangement of posters, clustered tightly in some areas and dispersing gradually into single, lone posters in others, follow noticeable ‘desire lines’, the shortcuts taken across an area of grassland, originating from the desire of one individual to take a new route; their initial footsteps inviting others to follow, gradually eroding the land and eventually establishing a new pathway. Indeed, like the first set of erosive footsteps, placing a poster in an uncharted space initiates the accumulation of more posters in that area.

Photography by Max Aldous-Fountain

Collaborative and competitive in equal measure, these posters are fragments of snatched conversation.

Turning off Cheltenham Road one afternoon, and entering quieter suburbia, I noticed a single sticker had been placed on a green rubbish bin. The next day, passing the same bin, three more stickers had joined the original: the unlikely beginnings of a new palimpsest. Through tracing these offcuts, these minor components of the larger mechanism of event promotion – the stickers and the posters, faded and ripped like pieces of mismatched fabric – a broader narrative of Bristol’s restless creativity unfolds. Collaborative and competitive in equal measure, these posters are fragments of snatched conversation. An overwhelming collation of overlapping colour, it is hard to study one event without becoming unwittingly transfixed by another. Regularly passing this wall on foot, this palimpsest of this city’s artistic output, is to connect directly with the ecosystem it represents. And in a climate where, by necessity, the city’s venues have fallen momentarily silent, I feel assured that whatever comes next will build upon the voices that have come before, the voices that remain memorialised along the length of this poster-plastered wall.

Have you got a favourite bit of printed history in Bristol? Let us know in the comments.

About Rife