Can Minorities Be Racist?

Tim investigates why her point of view on racism has changed as she’s moved from a British colony to Bristol

I’m Chinese, so growing up in Hong Kong (HK), I was part of the ruling race. Many of my close friends were mixed-race or non-Chinese, and I was aware of some prejudice against students and teachers who belonged to these groups from Chinese people – but I never really gave it much thought. I always believed these discriminatory actions and words were one-off incidents that stemmed from people simply being nasty. It wasn’t until moving to the UK and becoming a racial minority myself that I really understood the implications and effects of racist attitudes and occurrences and how damaging they can be.

As someone of Chinese heritage that grew up in Hong Kong, my identity, much like the city’s, is in constant tension with its Chinese roots and colonial history. I went to a French convent school where everything apart from Chinese-specific subjects was taught in English, so I admired everything to do with the English language. I watched English films and read English books, and the English countryside and towns I imagined from these classics were ingrained in my understanding of the world. I knew woefully little about non-Chinese and non-English cultures.

Chinese people were incredibly racist towards people of darker skin tones

In Hong Kong, Chinese people were incredibly racist towards people of darker skin tones. These people were usually people of South Asian, African, South American and Caribbean descent. Perhaps because of immigration and social mobility issues, the work they are perceived to do is usually blue-collared work. For example, Filipino and Indonesian people are stereotyped as being low-paid domestic helpers due to the large number of households that employ domestic workers from these countries, and this population’s representation in North American and British media (what my friends and I largely consumed) was disgustingly minimal. Due to what I saw or rather, didn’t see, I grew up thinking people with darker skin tones than my own were generally loud, violent, disruptive and to be avoided.

White people are considered generally rich, cool, highly regarded and respected

On the other hand, Chinese people (and dare I say the wider East Asian population in general), seem to see white people as being above the system. White people are considered generally rich, cool, highly regarded and respected. They are part of an international community that is above and separate from us. We strive to be like them, perhaps partly because our societies are so much shaped and built by them. Contemporary Japanese society and Korean culture were essentially shaped by the US, while Hong Kong and Singapore as we know them developed under heavy British influence. There’s an idolisation of ‘Western’ culture and reverence of white people – they’re different, they’re better, they’re softer spoken, well-educated and ‘civilised’.

‘I don’t want to sit next to them because they stink’

Whether we idolise or abhor races different to our own, there’s always a distinct sense of the ‘othering’ towards people who look, behave and sound different to ourselves: from my English or Northern European friends being stared at in awe in mainland China, to my Filipino and Indian friends in school dealing with Chinese classmates saying, ‘I don’t want to sit next to them because they stink’. Also, exclusion from political and activist causes due to language barriers, coupled with an attitude of ‘you wouldn’t understand because you’re not native Chinese,’ alienate many racial minorities in HK.

I see it in white people who claim they are only ‘joking’ about race when they call someone a ‘chink’ or use the n-word and p-word

I see many parallels between the racist mind-set of Chinese people in Hong Kong and the attitudes of English people in the UK. I have recent experiences of being ignored in group discussions, being talked over, of people who don’t look you in the eye when you’re speaking, and those who voice the exact same point that you made five minutes ago as if it’s a completely new concept they suddenly thought of. I see it in white people who claim they are only ‘joking’ about race when they call someone a ‘chink’ or use the n-word and p-word, when they claim they simply can’t be racist because they have an African or Chinese or Indian or Pakistani friend, as if knowing someone from a minority culture automatically exempts them from any responsibilities of ethics as the dominant race.

On one hand, I am a member of the East Asian diaspora in the UK. We have been historically whitewashed from history, and we are the invisible race that experiences racism, discrimination and prejudice. Vera Chok in Yellow and Daniel York in Kendo Nagasaki and Me – both curated by Nikesh Shukla in The Good Immigrant – discuss this in more depth. But on the other hand, I’ve also discovered a rivalry and discontentment within different racial minority groups. There’s this sense that East Asians are different and don’t identify as strongly as BME/BAME. Some East Asians see the BME label as unnecessary because they might not have experienced as much oppression and prejudice in relation to other racial minorities in the UK. Others, especially younger generations, don’t see why they should be part of the activism towards pushing for equality, or even care about any of the BME cause. Of course, there are exceptions, as with the BEA artists, actors and media networks led by Daniel York, Lucy Sheen, Christopher Chow and Daniel Tse.

East Asians also don’t like to talk about East Asian racism towards black people

East Asians also don’t like to talk about East Asian racism towards black people. There seems to be an assimilation of ourselves with white people in this country, a desire to be a model minority, to disassociate ourselves from the working class (a class we associate black people with). As Wei Ming Kam points out in her piece Beyond ‘Good’ Immigrants again curated as part of The Good Immigrant, we buy into this illusion that we are a solid middle-class model minority, that we have to be good immigrants that don’t stir shit up, are quiet and hardworking and do as we’re supposed to – unlike black people who are often considered violent, loud, rebellious by nature, and disruptive. For me, the dissonance among East Asian people and black people was particularly highlighted when Black Panther came out and there was dissatisfaction among Asians that black people always seem to get the spotlight when it comes to minority recognition. I have definitely fallen prey to the illusion that if you keep your head down and assimilate yourself as much as possible with the white mind-set and make yourself invisible, you wouldn’t be discriminated against. Of course, that’s not true. Instead of aligning ourselves with racist values, surely we should be supporting each other to combat and unlearn racism.

…if you keep your head down and assimilate yourself as much as possible with the white mind-set and make yourself invisible, you won’t be discriminated against

I continue to wander between two cultures: my Hong Kong origins where I am part of the privileged, middle class, majority race, and my current life in the UK, where I am part of the minority race, discriminated against, invisible, but still holding certain privileges (like not being assumed you’re violent by nature or a terrorist just by how you look and dress). It’s a strange world to navigate. I’m learning to stop my avoidance of racial issues, instead embracing it along with what it means to be a minority in this country. I can’t change how I look and I’m learning to be proud of my unique heritage and culture. I am also acknowledging my privilege and unlearning racist attitudes towards other racial minorities.

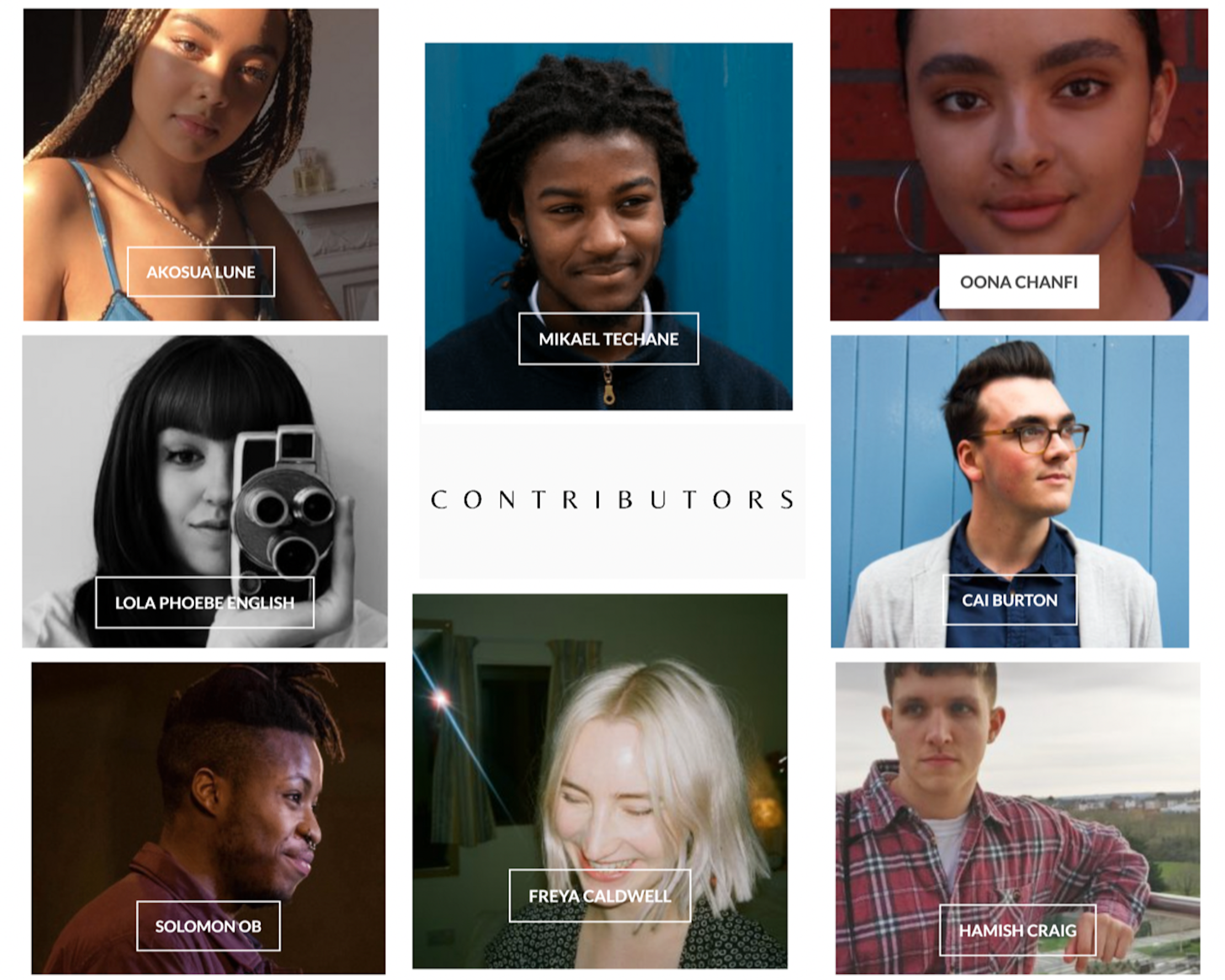

The first step towards demystifying and understanding is exposure. So, every day, I chat to my fellow journalists Ella and Mikael and try to learn more about their African and Caribbean heritage and culture, and every time I am around other racial minorities, I make sure to take the initiative to chat to them, get to know what work they do in Bristol, find out more about their experiences. Every day, I’m striving to learn a little more and unlearn a little more about them, and about me.

What do you think about race and cultural issues? Have you experienced changes in how you think about race as well? Let us know on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.