Story-Dwelling: The Big Adventure Games Revival

Cal Russell-Thompson reminisces about his favourite adventure games and points and clicks at its revival.

Ben, the leader of a biker gang, is framed for murder

‘Full Throttle’ is still one of my favourite games. I installed the thing when I was eight years old, pushing my rudimentary understanding of computers beyond its limit just to get it to run. After a long while the speakers began fizzing with the sound of a low, sustained ‘E’ note as a blue and grey sky burst into view, its clouds menacingly still. Ben, the leader of a biker gang is framed for murder.

In this fashion, the game introduced its central theme.

It’s a dynamic and gritty start to a game, and it might therefore seem jarring to note that Full Throttle isn’t an action game or a shooter, but a point-and-click adventure game. You navigate Ben through a moody post-apocalyptic American desert full of darkly comic characters, with your mouse, and it’s utterly brilliant. I was an eight-year-old wisecracking Hell’s Angel tasked with solving bizarro lateral thinking problems, talking my way out of awkward situations, and pushing people off their bikes.

Full Throttle, 1995. Image credit: LucasArts

To many, the 1990s is the golden age of adventure games.

To many, the 1990s is the golden age of adventure games. Even George Lucas, who did some pretty terrible things in the ‘90s, pumped money into them. LucasArts’ games told stories with wit, mystery and charm, and have a big cult following these days. These include ‘Full Throttle’, the swashbuckling pirate yarn ‘Monkey Island’, and the Mexican-film-noir-in-the-underworld pastiche ‘Grim Fandango‘. Meanwhile, rival studios such as Sierra, Revolution and Cyan provided fierce competition with their own adventure games.

However, adventure games were already in deep trouble by the time of Full Throttle’s release in 1995: 3D gaming had arrived, and so had the first major tranche of racers and shooters. Soon enough, playing a point-and-click game wasn’t an exciting prospect anymore. By the year 2000, all that remained were occasional gems like ‘Professor Layton’ and ‘Phoenix Wright’. The golden age was over.

Grim Fandango, 1998. Image Credit: LucasArts

Meanwhile, story and action drifted apart in these new 3D games.

Meanwhile, story and action drifted apart in these new 3D games. Even today, many games still tell stories through non-interactive videos. You’re free to play the game between story beats, but that’s it. This began as a way of showing off the muscle power of consoles; it’s ended up stifling the way stories are told in games.

Worse, sometimes the action itself jars with your sympathies: how can you root for Lara Croft or Nathan Drake when they’re killing so many people? This in particular seemed a step backward from adventure game protagonists, who were always in character. Try and do something they wouldn’t do, and they’d tell you: in ‘Grim Fandango’, Mannie laughs directly at you if you try to make him root around in a giant cat litter tray. He’d sooner break the fourth wall than be an inconsistent character.

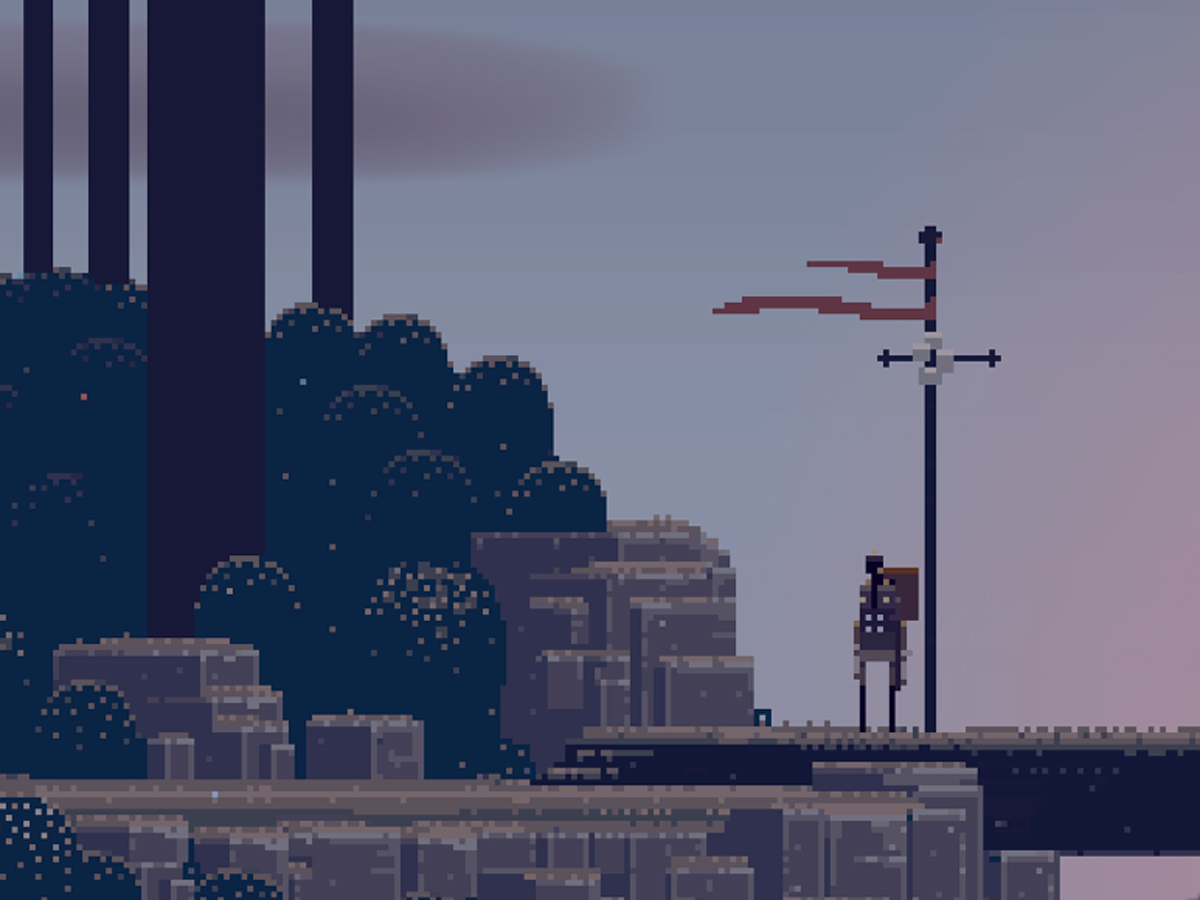

Sword & Sworcery EP, 2011. Image credit: Capybara Games

It’s this degree of narrative confidence now re-emerging at increasing speed…

It’s this degree of narrative confidence now re-emerging at increasing speed, with games like ‘Bioshock Infinite’ telling stories with stronger worlds and consistent characters whose actions have brutal repercussions. And so, naturally, adventure games themselves are returning. Recent years have seen ‘The Walking Dead‘ and ‘Game of Thrones‘ muscle their way into the adventure gaming scene. ‘Life Is Strange‘, ‘Broken Age‘ and the ‘Dreamfall Chapters‘ are slowly releasing episodic stories too. ‘Kentucky Route Zero‘ and ‘Sword & Sworcery EP‘ are perhaps the best adventure games of the last four years, with dark mysteries which twist and turn unpredictably.

Mystery is the key to all these games…

Mystery is the key to all these games: each has a case to solve, and you’re the detective. But these experiences don’t always have to be fictional. ‘It is only natural for us to use [games] not just for fiction but for non-fiction too,’ says Tomas Rawlings of Stokes Croft-based developer Auroch Digital, currently working on an interactive documentary in which the player investigates the Jack the Ripper murders. ‘We’re using games mechanics to tell a real-world story, so it’s us drawing from fictional devices in gaming.’

Like an adventure game, ‘Jack The Ripper: Shadow Over Whitechapel‘ uses game systems to combine gameplay and story as seamlessly as possible. However, Rawlings insists that ‘interactivity has to come first … Players want to feel they are part of the world, so making sure that the story fits around the interactions is key. Games are great ways to tell stories, but how you go about doing it is different; it’s less story-telling and more story-dwelling.’

…developers and gamers alike are beginning to rediscover a love of immersion in worlds.

Perhaps this is the main reason for the renaissance of thoughtful mysteries in games: developers and gamers alike are beginning to rediscover a love of immersion in worlds. As a part of that immersion, the boundaries between story and game, fiction and non-fiction must be blurred until one is indistinguishable from the other. Adventure games have returned precisely because they can help provide that experience – and it’s good to see them again.

Jack The Ripper: Shadow Over Whitechapel, 2015. Image credit: Auroch Digital

What’s your favourite adventure game? The bestest point-and-click? Let us know: @rifemag

Related Links: